|

||

|

||

|

Saturday, May 24, 2008

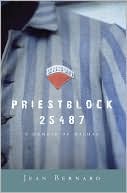

Father Jean Bernard's "Priestblock 25487: A Memoir of Dachau"

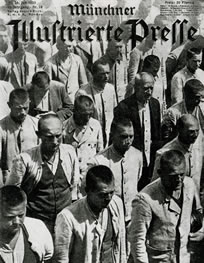

"There is little need to rehearse the conditions of their lives in the camp," says William O'Malley (The Priests of Dachau, "It was a hell before which Dante would stand mute." "There is little need to rehearse the conditions of their lives in the camp," says William O'Malley (The Priests of Dachau, "It was a hell before which Dante would stand mute."A good day was one on which you'd been beaten to your knees only once or twice; one small wad of bread and a cup of watery soup; 12 hours of hard labor, dragging the corpses to the roll call each morning and evening; warehoused at night in tiers, sleeping three to each lice-infested bunk; lugging one's soul from place to place in the fellowship of zombies; the cold, the filth, the endless degrading "hazing", the typhus, the inhuman joy when your best friend was beaten senseless and you were ignored. For some, hell lasted five years of days.  Priestblock 25487 contains the collected memoirs of one such priest from Luxembourg, Fr. Jean Bernard, arrested in 1941 for denouncing the Nazis. He was imprisoned from May 1941 to August 1942. Priestblock 25487 contains the collected memoirs of one such priest from Luxembourg, Fr. Jean Bernard, arrested in 1941 for denouncing the Nazis. He was imprisoned from May 1941 to August 1942.

Initially, the clergy were given "special treatment" -- apparently by request of the Pope: a ration of wine (administered under duress, if necessary); a loaf of bread split between four men; separate bunk accomodations. The celebration of Mass is even tolerated. This segregation has a downside, however -- keeping them in moral isolation and fostering resentment among the ranks. The "good times" come to an abrupt end in October. Breviaries and rosaries are confiscated; religious activity is prohibited and the clergy are made to join the general workforce. "Some people said that the Pope had given a strong speech on the radio, and the German Bishops had issued a public protest" -- a reminder that under the Nazi regime, outspoken resistance had immediate repercussions on those imprisoned. From there on out, chapter by chapter, Bernard's situation and that of his fellow priests grows progressively worse. The daily routine of the prisoner is described in harrowing detail. Backbreaking work and the performance of inane tasks, punctuated by arbitrary beatings and punishments meted out by sadistic guards. (Never mind the fate of the prisoners, the condition of the camp itself must be kept pristine in adherence to military order). Hunger is an ongoing battle -- as the supply of food dwindles, the acquisition of a single turnip, a dandelion, a scrap of cabbage or a seedling plucked from the compost heap is received with celebration. Those too weak to work are admitted to the infirmary, an even more hellish fate as the reader discovers. Throughout, Fr. Bernard encourages the spirits of his comrades, and at times (coverty) fulfills his priestly functions. There are also moments of striking clarity, where the light of Christian faith and divine grace pierces what seems an eternal night. Two accounts struck me in particular: the first is from early on, when Bernard is imprisoned, shortly after his arrest and awaiting his sentence: My neighbor taps on the wall. "Is it true you are saying Mass? — I'd like to say the responses. Would raise your voice a bit to say the prayers? And please knock three times before the consecration." The second from midway through, Christmas 1941: "I'm on gate duty today," Cappy whispers to me. We are returning from the assembly square on Christmas morning, and our column is marching alongside the German clergy's column for a brief moment.Priestblock 25487: A Memoir of Dachau  In 2004, The Ninth Day was released -- loosely based on Bernard's memoirs. According to the synopsis: Abbé Kremer is released from a living hell in the Dachau concentration camp and sent home to Luxembourg. Upon his arrival, he soon learns that this is not a reprieve or a pardon of his crime – voicing opposition to the Nazis’ racial laws – but that he has nine days to convince the bishop of Luxembourg to work with the Nazi occupiers. Gestapo Untersturmführer Gebhardt is under pressure from his superior to have the Abbé succeed in creating a rift between the Luxembourg church and the Vatican – or be transferred to duty in the death camps in the East. Gebhardt, a former Catholic seminarian, uses theological arguments to bring the Abbé around but when they don’t work he resorts to more draconian measures. The Abbé is torn between his conscience and his horror of returning to Dachau...Some clarification: Bernard's account of his leave in the book is much different than that of the film. This is not to say that Bernard isn't faced with the option of saving himself, fleeing or returning to camp of his own volition (avoiding repercussions to his fellow prisoners); or that he isn't grilled during an obligatory meeting at Gestapo headquarters about the status of his "re-education" (a great propaganda success, were it to be achieved) -- only that he is granted his suprise leave for a different reason, which I'll leave to the reader to discover. Related Priestblock 25487: A Memoir of Dachau

The Ninth Day

See also:

Labels: books

|

Against The Grain is the personal blog of Christopher Blosser - web designer

and all around maintenance guy for the original Cardinal Ratzinger Fan Club (Now Pope Benedict XVI).

Blogroll

Religiously-Oriented

"Secular"

|

|