|

||

|

||

|

Saturday, January 24, 2009

Vatican lifts excommunications on SSPX hierarchy; Bishop Bernard Fellay and District Superior for Germany apologize for Richard Williamson's remarks

From Vatican Radio comes the news that Holy See today has lifted the excommunications of the four bishops of the SSPX by a decree of the Congregation for Bishops.

Amy Welborn offers a good assessment of the situation and a roundup of responses to the Vatican's move -- among them the helpful post from the clerical blog Rationabile Obsequium (What precisely has the Pope done?) and this analysis from Carlos Palad of Rorate Caeli; a good aid in discerning what this means (an invitation to reconciliation with the Catholic Church); and more importantly what it does not ("The lifting of the excommunications on the SSPX bishops does not signify that the SSPX is back in full communion with the Holy See"). The ball is now in the SSPX's court.

Earlier this month, SSPX Bishop Williamson gave an interview to the Swedish press, in which he espoused his oft-repeated view that none of [the Jews] died as a result of gas in gas chambers." Williamson has previously endorsed the anti-semitic forgery Protocols of the Elders of Zion ("God put into men's hands the Protocols of the Sages of Sion... if men want to know the truth, but few do") and has asserted that the Jews are fighting for world domination "to prepare the Anti-Christ's throne in Jerusalem." In the past, he has also indulged in 9/11 conspiracy theorizing and denounced Vatican II as "the religion of man, of man put in the place of God ... it's a new religion, dressed up to look like the Catholic religion, but it's not." (See Catholic Herald March 5, 2008) and "The Politics of Bishop Richard Williamson" (Fringewatch January 25, 2006). I fear that the Pope's gesture will not go over well with the Jewish people or those sympathetic to the betterment of Christian-Jewish relations. Some will see the lifting of excommunication without a concurrent demand for a change of mind and heart on the part of avowed anti-semites like Williamson as a tacit acceptance. Writing to Cardinal Kasper, President of the Pontifical Commission on Religious Relations With the Jews, Abraham Foxman of the Anti-Defamation league expressed his concern that lifting Bishop Williamson's excommunication "could become a source of great tension between Catholics and Jews.": "The re-admittance to full communion of a bishop who appears to publicly reject key teachings of the Second Vatican Council could provide succor to those whose views threaten the Jewish people and the Church's desire to improve and deepen its relationship with us to benefit all mankind." From my understanding Williamson's views have scandalized some within the SSPX; however, Bishop Fellay has taken a 'hands off' approach in his handling of the controversy. In a stern reply to the Swedish television studio, he castigated them for their "vile attempts" to question Williamson's views on the Holocaust, stating: It is obvious that a bishop can only speak about questions of faith and morals with any ecclesial authority. If he deals with secular issues he is personally responsible for his own private opinions. The Society I am governing has no authority to address such issues, or will it ever claim such authority.No doubt that if the SSPX has any desire to reconcile with Rome, particularly after Pope Benedict's significant gesture in their direction, they will have to confront the obstacle of Bishop Richard Williamson.

Labels: benedict, extremism, traditionalism

Saturday, August 02, 2008

Benedict in Bressanone

Pope Benedict XVI sits on a bench on July 31, 2008 in the garden of his holiday residence in Bressanone. Source: Getty Images

Labels: benedict

Thursday, April 17, 2008

Benedict's Address to the American People at the White House

Text of the address given by Pope Benedict XVI on the South Lawn of the White House, April 19th, 2008

Mr. President,

Thank you for your gracious words of welcome on behalf of the people of the United States of America. I deeply appreciate your invitation to visit this great country. My visit coincides with an important moment in the life of the Catholic community in America: the celebration of the two-hundredth anniversary of the elevation of the country's first Diocese – Baltimore – to a metropolitan Archdiocese, and the establishment of the Sees of New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Louisville. Yet I am happy to be here as a guest of all Americans. I come as a friend, a preacher of the Gospel and one with great respect for this vast pluralistic society. America's Catholics have made, and continue to make, an excellent contribution to the life of their country. As I begin my visit, I trust that my presence will be a source of renewal and hope for the Church in the United States, and strengthen the resolve of Catholics to contribute ever more responsibly to the life of this nation, of which they are proud to be citizens.

From the dawn of the Republic, America's quest for freedom has been guided by the conviction that the principles governing political and social life are intimately linked to a moral order based on the dominion of God the Creator. The framers of this nation's founding documents drew upon this conviction when they proclaimed the "self-evident truth" that all men are created equal and endowed with inalienable rights grounded in the laws of nature and of nature's God. The course of American history demonstrates the difficulties, the struggles, and the great intellectual and moral resolve which were demanded to shape a society which faithfully embodied these noble principles. In that process, which forged the soul of the nation, religious beliefs were a constant inspiration and driving force, as for example in the struggle against slavery and in the civil rights movement. In our time too, particularly in moments of crisis, Americans continue to find their strength in a commitment to this patrimony of shared ideals and aspirations. In the next few days, I look forward to meeting not only with America's Catholic community, but with other Christian communities and representatives of the many religious traditions present in this country. Historically, not only Catholics, but all believers have found here the freedom to worship God in accordance with the dictates of their conscience, while at the same time being accepted as part of a commonwealth in which each individual and group can make its voice heard. As the nation faces the increasingly complex political and ethical issues of our time, I am confident that the American people will find in their religious beliefs a precious source of insight and an inspiration to pursue reasoned, responsible and respectful dialogue in the effort to build a more humane and free society.

Freedom is not only a gift, but also a summons to personal responsibility. Americans know this from experience – almost every town in this country has its monuments honoring those who sacrificed their lives in defense of freedom, both at home and abroad. The preservation of freedom calls for the cultivation of virtue, self-discipline, sacrifice for the common good and a sense of responsibility towards the less fortunate. It also demands the courage to engage in civic life and to bring one's deepest beliefs and values to reasoned public debate. In a word, freedom is ever new. It is a challenge held out to each generation, and it must constantly be won over for the cause of good (cf. Spe Salvi, 24). Few have understood this as clearly as the late Pope John Paul II. In reflecting on the spiritual victory of freedom over totalitarianism in his native Poland and in eastern Europe, he reminded us that history shows, time and again, that "in a world without truth, freedom loses its foundation", and a democracy without values can lose its very soul (cf. Centesimus Annus, 46). Those prophetic words in some sense echo the conviction of President Washington, expressed in his Farewell Address, that religion and morality represent "indispensable supports" of political prosperity.

The Church, for her part, wishes to contribute to building a world ever more worthy of the human person, created in the image and likeness of God (cf. Gen 1:26-27). She is convinced that faith sheds new light on all things, and that the Gospel reveals the noble vocation and sublime destiny of every man and woman (cf. Gaudium et Spes, 10). Faith also gives us the strength to respond to our high calling, and the hope that inspires us to work for an ever more just and fraternal society. Democracy can only flourish, as your founding fathers realized, when political leaders and those whom they represent are guided by truth and bring the wisdom born of firm moral principle to decisions affecting the life and future of the nation.

For well over a century, the United States of America has played an important role in the international community. On Friday, God willing, I will have the honor of addressing the United Nations Organization, where I hope to encourage the efforts under way to make that institution an ever more effective voice for the legitimate aspirations of all the world's peoples. On this, the sixtieth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the need for global solidarity is as urgent as ever, if all people are to live in a way worthy of their dignity – as brothers and sisters dwelling in the same house and around that table which God's bounty has set for all his children. America has traditionally shown herself generous in meeting immediate human needs, fostering development and offering relief to the victims of natural catastrophes. I am confident that this concern for the greater human family will continue to find expression in support for the patient efforts of international diplomacy to resolve conflicts and promote progress. In this way, coming generations will be able to live in a world where truth, freedom and justice can flourish – a world where the God-given dignity and rights of every man, woman and child are cherished, protected and effectively advanced. Mr. President, dear friends: as I begin my visit to the United States, I express once more my gratitude for your invitation, my joy to be in your midst, and my fervent prayers that Almighty God will confirm this nation and its people in the ways of justice, prosperity and peace. God bless America! Labels: benedict

Thursday, April 10, 2008

Pope Benedict's appreciation for American religious freedom

Cross-posted to Benedict in America - Chris]

"I think he's really fascinated by the city and what it represents," says Raphaela Schmid, a Rome-based German with the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, who knows him. "It's about people being two things at once, like Italian Americans or Chinese Americans. He's interested in that idea of coexistence."Israely disputes the idea that the so-called "Vatican enforcer" harbors an antagonism toward "the democratic, pluralistic values that constitute (on our good days) the American brand": ... A survey of the 80-year-old Pontiff's writings over the decades and testimonies from those who know him suggests that Benedict has a soft spot for Americans and finds considerable value in his U.S. church, the third largest Catholic congregation in the world. Most intriguing, he entertains a recurring vision of an America we sometimes lose sight of: an optimistic and diverse but essentially pious society in which faiths and a faith-based conversation on social issues are kept vital by the Founding Fathers' decision to separate church and state. It's not a stretch to say the Pope sees in the U.S.--or in some kind of idealized version of it--a civic model and even an inspiration to his native EuropeAccording to Israely, during his stint as peritus during the Second Vatican Council, Joseph Ratzinger was sympathetic to the arguments of the U.S. delegation (John Courtney Murray?) in the debate over religious freedom: Conservatives opposed [religious freedom]: states must sponsor faith, and the faith should be Roman Catholic. The Americans argued that religious liberty was morally imperative and--from experience--that in a multireligious state, Catholicism could best thrive when the government could not play favorites. The council sided with them, and Ratzinger, anticipating a world composed of jostling religious pluralities, heartily approved. In a 1966 analysis, he wrote, "In a critical hour, Council leadership passed from Europe to the young Churches of America and [their allies]," who "were really opening up the way to the future."Israely admits that Ratzinger's appreciation for the American conception of religious freedom "did not extend to an acceptance that all roads to salvation are equal or to a license for democracy within his church" (how could it, really?) -- nonetheless: [Benedict] came to respect the way Catholic leaders in the U.S. went about their business. A current (non-American) CDF official notes that the U.S. church is the only one that keeps a "serious" doctrinal office rather than an unthinking rubber stamp or an old-boys' club; when conflicts arise, its bishops are actually prepared to discuss them. Moreover, says Levada, "he seems to recognize that we're plain speakers. We don't hide behind words."  Israely cites as a prominent example of the Pope's appreciation for America expressed in Without Roots, his 2004 exchange with the president of the Italian Senate, Marcello Pera: Israely cites as a prominent example of the Pope's appreciation for America expressed in Without Roots, his 2004 exchange with the president of the Italian Senate, Marcello Pera:It bemoans the European Union's refusal to acknowledge Christianity in a draft constitution, and Pera wonders about bringing back some kind of multidenominational "Christian civil religion." In response, Ratzinger cites Alexis de Tocqueville's Democracy in America and makes the case that America's Founding Fathers were pious men of different denominations who wrote the First Amendment prohibiting state establishment (that is, sponsorship) of religion precisely because sponsorship would stifle all non-established creeds--which they hoped would achieve full and varied flower.As far as his Apostolic Journey to America is concerned, Israely believes Benedict will be "less interested in scolding American Catholics than in talking up 'new religious communities ... being formed who quite consciously aim at a complete fulfillment of the demands of religious life'" -- schools of burgeoning Catholic orthodoxy like Thomas Aquinas College in Santa Paula, Calif.; Christendom College in Front Royal, Va.; and Ave Maria University in Ave Maria, Fla -- "eruptions of non-state-related religious vitality at which he thinks we excel." There are a few points in Israely's article which betray his liberal sympathies -- as when he says "There are times when Benedict's love affair with American religious pluralism seems a bit naive, especially when it clashes with his nonnegotiable doctrinal stands" or "downplaying the idea that Catholics may legitimately balance church teaching against the demands of their conscience." But on the whole I think it worth the read. Israely closes: John Paul II described faith and reason as the twin wings that lift the church. And yet a balanced takeoff has remained elusive. The U.S. is one of the few places where it seems to happen regularly. "America is simultaneously a completely modern and a profoundly religious place. In the world, it is unique in this," says a senior Vatican official. "And Ratzinger wants to understand how those two aspects can coexist." Almost all the things the Pope likes about us--our faith in the real value of plainspokenness, our pluralistic piety and even our wrangles around applying religiously grounded moral principles to increasingly abstruse science--can be understood in light of this quest. If he finds answers in the U.S., they could help define his papacy. Further Reading Ratzinger/Benedict on "Separation of Church & State"

Monday, March 24, 2008

Benedict in America

Blogging will be sparse on Against The Grain -- at least until April 20 -- as I will be devoting most of my attention to chronicling Pope Benedict XVI's 2008 Apostolic Journey to the United States, compiling news, commentary and resources on the papal visit with occasional editorial criticism. Blogging will be sparse on Against The Grain -- at least until April 20 -- as I will be devoting most of my attention to chronicling Pope Benedict XVI's 2008 Apostolic Journey to the United States, compiling news, commentary and resources on the papal visit with occasional editorial criticism.

Thus far it has been chiefly a one-man effort, but if anybody's so inspired to join me in this project, let me know. I'd love to make this a like-minded effort (along the lines of Catholics in the Public Square and bring in perspectives other than my own. =) Labels: benedict

Sunday, January 20, 2008

Pope Benedict, Sapienza University and the Intolerance of Radical Secularism

La Sapienza University is the largest European university and the most ancient of Rome's three public universities. It was founded in 1303 by Pope Boniface VIII -- in 1870, it was secularized and became the university of the capital of Italy. [Source: Wikipedia]. This year, Pope Benedict XVI was scheduled to speak to 1,000 hand-picked guests in the Aula Magna, the main lecture hall, at the inauguration of the academic year.

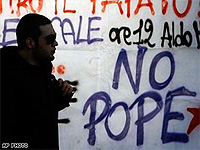

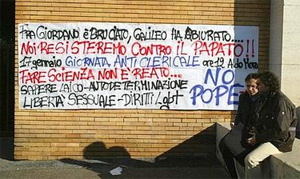

A hundred militant left wing students had occupied the office of Professor Renato Guarini, the university rector, to demand that the papal visit be cancelled because of Benedict's "obscurantist" stand on science in general and the Church's treatment of Galileo as a heretic in particular. Sixty-seven science professors and lecturers at La Sapienza signed a letter to Professor Guarini calling on him to scrap the visit. Professor Guarini said the Pope was "saddened" by the protests.  According to Reuters: According to Reuters:. . . The first day on Monday revolved around an "anti-clerical" meal of bread, pork and wine and a banner reading: "Knowledge needs neither fathers nor priests". In defense of Galileo?

In their letter the La Sapienza scientists, including Andrea Frova, author of a study of Galileo, and Carlo Maiani, the head of the Italian National Council for Research, said they felt "offended and humiliated" by a statement made in 1990 by the then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger suggesting the trial of Galileo for heresy because of his support for the Copernican system was justified in the context of the time.Unfortunately, the Times reporting (which is indicative of the understanding of the Sapienza faculty) is factually incorrect and reveals a gross misunderstanding of what Ratzinger actually said.  From L'Osservatore Romano, Professor Giorgio Israel (translation by the Papa Ratzinger Forum): From L'Osservatore Romano, Professor Giorgio Israel (translation by the Papa Ratzinger Forum):They accuse him of having said - in a lecture he gave at La Sapienza on February 15, 1990 {cfr J. Ratzinger, Wendezeit für Europa? Diagnosen und Prognosen zur Lage von Kirche und Welt, Einsiedeln-Freiburg, Johannes Verlag, 1991, pp. 59 e 71) - a statement that was actually from the philosopher of science, Paul Feyerabend: "In the time of Galileo, the Church was much more faithful to reason than Galileo himself. The trial of Galileo was reasonable and just."As John Allen Jr. remarks: In a nutshell, therefore, Benedict is being faulted by the physics professors for quoting somebody else's words, which his full text suggests he does not completely share. (Readers who remember Regensburg can be forgiven a sense of déjà-vu.) Also by way of John Allen, Jr., the comments by then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger on the Galileo case, excerpted from Benedict cancels -- and turns the tables on Sapienza protestors January 16, 2008

Esteemed Rector,the Holy Father had gladly accepted your invitation to visit the Università degli Studi "La Sapienza", to offer in this way a sign of affection and of the high regard in which he holds this illustrious institution, which originated centuries ago at the behest of his venerated predecessor. From AsiaNews.it, translation of the speech Benedict XVI planned to deliver Thursday at La Sapienza University in Rome.. According to Zenit News Service, Benedict's address was read by another professor during the inauguration, to much acclaim: During the inauguration ceremony, a professor read the discourse the Holy Father had prepared for the occasion. A standing ovation and students' shouts of "Long live the Pope" followed the reading. Meanwhile, Italian leaders voiced their dismay at the Pope's cancellation (Catholic World News): Italian president Giorgio Napolitano released a statement condemning the "inadmissible intolerance" shown by the campus protestors, who had planned to greet the Pope with loud rock music, anti-clerical posters, and parades of militant homosexuals. Prime Minister Romano Prodi said that the protests had "provoke unacceptable tensions and created a climate that does not honor Italy's traditions of civility and tolerance."

"So there are three places where the pope cannot go: Moscow, Beijing, and the university of Rome", commented one of the young people present at the audience. "If Benedict does not go to La Sapienza, La Sapienza comes to Benedict", read one of the banners that the young people raised. January 17, 2008

"Next Sunday's event will be a moment of prayer, any other motivation in the people joining us at St. Peter's Square would be unwelcome and out of place," Cardinal Ruini told the Vatican daily L'Osservatore Romano. In an interview with 'Corriere della Sera, Ruini also remarked that "some signs of solidarity" with the Pope by attendees of Sappienza University had come too late. January 18, 2008

Commentary

Labels: benedict, extremism, ratzinger, secularism

Sunday, December 30, 2007

Thoughts on Pope Benedict XVI's Spe Salvi ("Saved in Hope")

According to John Allen Jr., Benedict XVI's second encyclical Spe Salvi might be considered a 'Greatest Hits' collection of core Ratzinger ideas -- "a compilation of core concerns, his idees fixes over almost sixty years now of theological reflection": According to John Allen Jr., Benedict XVI's second encyclical Spe Salvi might be considered a 'Greatest Hits' collection of core Ratzinger ideas -- "a compilation of core concerns, his idees fixes over almost sixty years now of theological reflection":

Having just finished Benedict's second encyclical today -- in between naps, as is the tendency these days with a new youngster in the household -- I'm really at a loss as to what to offer in the way of blogging or commentary. I read it online, but suffice to say it's one of those texts where if I had a highlighter, I'd easily run out of ink. Then again, that's often the case when reading Ratzinger / Benedict XVI. So what follows are some notes, impressions and passages which particularly struck me, perhaps as impetus for discussion by our readers. Benedict begins by exploring the relationship between hope and faith in the Christian scriptures and the early Church. Benedict poses the question each of us must ask ourselves: The present, even if it is arduous, can be lived and accepted if it leads towards a goal, if we can be sure of this goal, and if this goal is great enough to justify the effort of the journey. Now the question immediately arises: what sort of hope could ever justify the statement that, on the basis of that hope and simply because it exists, we are redeemed? And what sort of certainty is involved here? In sections 10-12 Benedict addresses the human condition without hope, the dual fascination and repulsion at the prospect of our soul's immortality; he addresses to some understandable misconceptions one might have concerning the meaning of "eternal life": The term “eternal life” is intended to give a name to this known “unknown”. Inevitably it is an inadequate term that creates confusion. “Eternal”, in fact, suggests to us the idea of something interminable, and this frightens us; “life” makes us think of the life that we know and love and do not want to lose, even though very often it brings more toil than satisfaction, so that while on the one hand we desire it, on the other hand we do not want it. To imagine ourselves outside the temporality that imprisons us and in some way to sense that eternity is not an unending succession of days in the calendar, but something more like the supreme moment of satisfaction, in which totality embraces us and we embrace totality—this we can only attempt. It would be like plunging into the ocean of infinite love, a moment in which time—the before and after—no longer exists. We can only attempt to grasp the idea that such a moment is life in the full sense, a plunging ever anew into the vastness of being, in which we are simply overwhelmed with joy. This is how Jesus expresses it in Saint John's Gospel: “I will see you again and your hearts will rejoice, and no one will take your joy from you” (16:22). We must think along these lines if we want to understand the object of Christian hope, to understand what it is that our faith, our being with Christ, leads us to expect. Modernity and "the ideology of human progress" Benedict asks: "How could the idea have developed that Jesus's message is narrowly individualistic and aimed only at each person singly? How did we arrive at this interpretation of the “salvation of the soul” as a flight from responsibility for the whole, and how did we come to conceive the Christian project as a selfish search for salvation which rejects the idea of serving others?" -- this is a familiar charge that is, with respect to some articulations of Christianity, legitimate. Benedict looks to "the modern age", when spiritual concerns were supplanted by scientific knowledge and man embraced "the ideology of human progress"; where reason and freedom were heralded "to guarantee by themselves, by virtue of their intrinsic goodness, a new and perfect human community." (This seduction of humanity by positivism and the reduction of reality to techne is another familiar theme in Ratzinger, discussed for instance in the forward to Introduction to Christianity). Benedict looks at the French Revolution ("an attempt to establish the rule of reason and freedom as a political reality") and Marxism ("with the fall of political power and the socialization of means of production, the new Jerusalem would be realized") -- as representative of modern man's futile attempts to establish the 'Kingdom of God' on earth: Once the truth of the hereafter had been rejected, it would then be a question of establishing the truth of the here and now. The critique of Heaven is transformed into the critique of earth, the critique of theology into the critique of politics. Progress towards the better, towards the definitively good world, no longer comes simply from science but from politics—from a scientifically conceived politics that recognizes the structure of history and society and thus points out the road towards revolution, towards all-encompassing change. In section 21, Benedict gives the perfect paragraph-length summary of the ambitions of Marxism and where it failed: Marx not only omitted to work out how this new world would be organized—which should, of course, have been unnecessary. His silence on this matter follows logically from his chosen approach. His error lay deeper. He forgot that man always remains man. He forgot man and he forgot man's freedom. He forgot that freedom always remains also freedom for evil. He thought that once the economy had been put right, everything would automatically be put right. His real error is materialism: man, in fact, is not merely the product of economic conditions, and it is not possible to redeem him purely from the outside by creating a favourable economic environment. Regensburg Revisited

If progress, in order to be progress, needs moral growth on the part of humanity, then the reason behind action and capacity for action is likewise urgently in need of integration through reason's openness to the saving forces of faith, to the differentiation between good and evil. Only thus does reason become truly human. The Social Dimensions of Spe Salvi Benedict calls for "a self-critique of modernity in dialogue with Christianity"; Christians too must "learn anew in what their hope truly consists, what they have to offer to the world and what they cannot offer. Flowing into this self-critique of the modern age there also has to be a self-critique of modern Christianity, which must constantly renew its self-understanding setting out from its roots." I'm struck by Benedict's addition of the phrase "what Christianity cannot offer" -- it is opportune, given the myriad presentations of Christianity in our age, from televangelists preaching a "gospel of wealth" and material success to those for whom Christian praxis is reduced to a politicized, revolutionary program for class warfare. Benedict is reputedly working on a third encyclical devoted to social issues, but I found this section on "the true shape of Christian Hope" very relevant: Material progress is incremental. Man slowly gains a mastery of technique and power over his natural surroundings. But we cannot speak similarly of humanity's moral evolution: . . . in the field of ethical awareness and moral decision-making, there is no similar possibility of accumulation for the simple reason that man's freedom is always new and he must always make his decisions anew. These decisions can never simply be made for us in advance by others—if that were the case, we would no longer be free. Freedom presupposes that in fundamental decisions, every person and every generation is a new beginning.We can learn from the "lessons of history," the knowledge and "moral treasury" of previous generations -- or we can choose to reject it. This responsibility falls upon each generation. What are the implications? -- First, according to Benedict: The right state of human affairs, the moral well-being of the world can never be guaranteed simply through structures alone, however good they are. Such structures are not only important, but necessary; yet they cannot and must not marginalize human freedom. Even the best structures function only when the community is animated by convictions capable of motivating people to assent freely to the social order."Secondly: "Since man always remains free and since his freedom is always fragile, the kingdom of good will never be definitively established in this world. Anyone who promises the better world that is guaranteed to last for ever is making a false promise; he is overlooking human freedom. Freedom must constantly be won over for the cause of good. Free assent to the good never exists simply by itself. If there were structures which could irrevocably guarantee a determined—good—state of the world, man's freedom would be denied, and hence they would not be good structures at all."Consequently: ... every generation has the task of engaging anew in the arduous search for the right way to order human affairs; this task is never simply completed. Yet every generation must also make its own contribution to establishing convincing structures of freedom and of good, which can help the following generation as a guideline for the proper use of human freedom; hence, always within human limits, they provide a certain guarantee also for the future. In other words: good structures help, but of themselves they are not enough. Man can never be redeemed simply from outside.I could not help but see in this section shades of Benedict's critique of certain aspects of liberation theology and it's call for the overthrow of "structures of injustice" and a reduction of the gospel to "politico-messianic hope and praxis" (see Preliminary Notes on Liberation Theology by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, circa. 1984). There is present in this encyclical an "Augustianian realism" (characteristically Ratzinger) -- a lucid awareness of man's capacity for good and evil, and the inherent limitations placed upon man's striving by his nature. Thus we are reminded that our scientific and technological achievements "opens up appalling possibilities for evil—possibilities that formerly did not exist. . . . If technical progress is not matched by corresponding progress in man's ethical formation, in man's inner growth (cf. Eph 3:16; 2 Cor 4:16), then it is not progress at all, but a threat for man and for the world." Self-Centered Salvation?

Our relationship with God is established through communion with Jesus—we cannot achieve it alone or from our own resources alone. The relationship with Jesus, however, is a relationship with the one who gave himself as a ransom for all (cf. 1 Tim 2:6). Being in communion with Jesus Christ draws us into his “being for all”; it makes it our own way of being. He commits us to live for others, but only through communion with him does it become possible truly to be there for others, for the whole.Referring to Maximus the Confessor - this love of God and communion in Christ manifests itself in charity to others, is essentially other-oriented: "Love of God leads to participation in the justice and generosity of God towards others. Loving God requires an interior freedom from all possessions and all material goods: the love of God is revealed in responsibility for others. . . . Christ died for all. To live for him means allowing oneself to be drawn into his being for others." In what does our redemption consist? "It is not science that redeems man," says Benedict. Rather, "man is redeemed by love." Not a merely human love subject to fickleness and dissolution, but an everlasting and unconditional love: "He needs the certainty which makes him say: “neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rom 8:38- 39). If this absolute love exists, with its absolute certainty, then—only then—is man “redeemed”, whatever should happen to him in his particular circumstances. This is what it means to say: Jesus Christ has “redeemed” us. Through him we have become certain of God, a God who is not a remote “first cause” of the world, because his only-begotten Son has become man and of him everyone can say: “I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me” (Gal 2:20). . . . Prayer as Response of Christian Hope

To pray is not to step outside history and withdraw to our own private corner of happiness. When we pray properly we undergo a process of inner purification which opens us up to God and thus to our fellow human beings as well. In prayer we must learn what we can truly ask of God—what is worthy of God. We must learn that we cannot pray against others. We must learn that we cannot ask for the superficial and comfortable things that we desire at this moment—that meagre, misplaced hope that leads us away from God. We must learn to purify our desires and our hopes. We must free ourselves from the hidden lies with which we deceive ourselves. God sees through them, and when we come before God, we too are forced to recognize them. . . .Prayer can never be merely individual or self-preoccupied; genuine prayer is that which turns us toward others, in solidarity with our neighbor and communion in the Church: "For prayer to develop this power of purification, it must on the one hand be something very personal, an encounter between my intimate self and God, the living God. On the other hand it must be constantly guided and enlightened by the great prayers of the Church and of the saints, by liturgical prayer, in which the Lord teaches us again and again how to pray properly. We become capable of the great hope, and thus we become ministers of hope for others. Hope in a Christian sense is always hope for others as well. It is an active hope, in which we struggle to prevent things moving towards the “perverse end”. It is an active hope also in the sense that we keep the world open to God. Only in this way does it continue to be a truly human hope." Benedict on human suffering In sections 35-40, he embarks on a profound meditation on human suffering ("The true measure of humanity is essentially determined in relationship to suffering and to the sufferer") as a context for Christian hope: "It is not by fleeing from suffering that we are healed, but rather by our capacity for accepting it, maturing through it and finding meaning through union with Christ, who suffered with infinite love . . . A society unable to accept its suffering members and incapable of helping to share their suffering and to bear it inwardly through “com-passion” is a cruel and inhuman society. . . . the capacity to accept suffering for the sake of goodness, truth and justice is an essential criterion of humanity."Needless to say, it is only through the transformative hope that God brings that we as Christians can embrace suffering in this manner. Here Benedict recommends a revival of the practice of offering up our daily inconveniences and sufferings in Christ, an expression of our hope: What does it mean to offer something up? Those who did so were convinced that they could insert these little annoyances into Christ's great “com-passion” so that they somehow became part of the treasury of compassion so greatly needed by the human race. In this way, even the small inconveniences of daily life could acquire meaning and contribute to the economy of good and of human love. Maybe we should consider whether it might be judicious to revive this practice ourselves.Benedict devotes the latter section of his encyclical (sections 40-48) on the Last Judgement as a manifestation of Christian hope (together with a rich, theological exploration of Purgatory and man's purification from sin in Chrisitan thought). "I am convinced," says Benedict, "that the question of justice constitutes the essential argument, or in any case the strongest argument, in favour of faith in eternal life." The following passage offers much food for thought (and some questions as well): 47. Some recent theologians are of the opinion that the fire which both burns and saves is Christ himself, the Judge and Saviour. The encounter with him is the decisive act of judgement. Before his gaze all falsehood melts away. This encounter with him, as it burns us, transforms and frees us, allowing us to become truly ourselves. All that we build during our lives can prove to be mere straw, pure bluster, and it collapses. Yet in the pain of this encounter, when the impurity and sickness of our lives become evident to us, there lies salvation. His gaze, the touch of his heart heals us through an undeniably painful transformation “as through fire”. But it is a blessed pain, in which the holy power of his love sears through us like a flame, enabling us to become totally ourselves and thus totally of God. In this way the inter-relation between justice and grace also becomes clear: the way we live our lives is not immaterial, but our defilement does not stain us for ever if we have at least continued to reach out towards Christ, towards truth and towards love. Indeed, it has already been burned away through Christ’s Passion. At the moment of judgement we experience and we absorb the overwhelming power of his love over all the evil in the world and in ourselves. The pain of love becomes our salvation and our joy. It is clear that we cannot calculate the “duration” of this transforming burning in terms of the chronological measurements of this world. The transforming “moment” of this encounter eludes earthly time-reckoning-it is the heart’s time, it is the time of “passage” to communion with God in the Body of Christ. The judgement of God is hope, both because it is justice and because it is grace. If it were merely grace, making all earthly things cease to matter, God would still owe us an answer to the question about justice-the crucial question that we ask of history and of God. If it were merely justice, in the end it could bring only fear to us all. The incarnation of God in Christ has so closely linked the two together-judgement and grace-that justice is firmly established: we all work out our salvation “with fear and trembling” (Phil 2:12). Nevertheless grace allows us all to hope, and to go trustfully to meet the Judge whom we know as our “advocate”, or parakletos (cf. 1 Jn 2:1). Benedict closes his encyclical with a beautiful homage to our Holy Mother Mary, the exemplification of Christian hope: "With her 'yes' she opened the door of our world to God himself; she became the living Ark of the Covenant, in whom God took flesh, became one of us, and pitched his tent among us (cf. Jn 1:14)." Additional Commentary on Spe Salvi

The Catholic News Agency reports that over one million copies the new encyclical by Pope Benedict XVI, Spe Salvi, have been sold since it was released on November 30.

Friday, November 30, 2007

Pope Benedict's 2nd Encyclical - Spe Salvi - "On Christian Hope"

Full text of Pope Benedict XVI's second encyclical, Spe Salvi: On Christian Hope.

Full text of Pope Benedict XVI's second encyclical, Spe Salvi: On Christian Hope.

Some Analysis & Coverage

More to be compiled as we go along, but to echo St. Augustine: Tolle Lege! Labels: benedict

Thursday, November 29, 2007

Further Responses to "A Common Word"

[This post is a continuation of a discussion of the recent "open letter to the Pope" [and Christian community at large] by 138 Muslim scholars and reactions -- prior posts in this series: "A Common Word" and Christian-Muslim Dialogue 10/27/07; Fr. Christian Troll: Response to "A Common Word" 10/28/07]

Magister: Pope and Muslims "at a great distance" Sandro Magister turns his attention to the "open letter to the Pope" (and all Christians) -- entitled "A Common Word Between Us and You" -- from Muslim scholars, and speculates: Why Benedict XVI Is So Cautious with the Letter of the 138 Muslims (www.Chiesa November 26, 2007): Benedict XVI and the directors of the Holy See appear more cautious and reserved toward this flurry of dialogue.  Magister goes on to examine the kind of dialogue that Pope Benedict XVI wants -- as conveyed in a passage of his Christmas address to the Roman curia, on December 22, 2006: Magister goes on to examine the kind of dialogue that Pope Benedict XVI wants -- as conveyed in a passage of his Christmas address to the Roman curia, on December 22, 2006:"In a dialogue to be intensified with Islam, we must bear in mind the fact that the Muslim world today is finding itself faced with an urgent task. This task is very similar to the one that has been imposed upon Christians since the Enlightenment, and to which the Second Vatican Council, as the fruit of long and difficult research, found real solutions for the Catholic Church.Says Magister: "The letter of the 138 contains no trace of this proposal that Benedict XVI issued to the Muslim world in December one year ago. This is a sign that there is truly a great distance between the visions of these two."

"The Vatican will respond positively, and quite soon," Dakar Cardinal Theodore-Adrien Sarr told Reuters on Sunday, November 25, during a ceremony to install 23 new members of the College of Cardinals.Nayed vs. Tauran: No Dialogue Possible?

Numerous sources have cited Cardinal Tauran's rather blunt dismissal of the possibility of theological dialogue with Muslims, because "Muslims do not accept the possibility of discussing the Quran, because it is written, they say, as dictated by God" and "with such a strict interpretation, it is difficult to discuss the content of faith." Arif Ali Nayed, one of the original signers of "A Common Word", responded in an interview with Cindy Wooden of the Catholic News Service (Islamica Magazine, No. 20): Cardinal Tauran’s statement to Le Croix was very disappointing indeed. It came at a time of high expectation of responsiveness, and on the eve of the important Naples Sant’Egidio encounter. Many people were expecting Pope Benedict XVI to say something positive about the Muslim scholars’ initiative. Alas, a truly historic opportunity for a loving embrace was simply missed.Nayed goes on to specifically rebut Tauran's charges, noting the double irony in that it "accuses Muslims of an imaginary theological/hermeneutical closure that is more appropriately attributable to the Vatican’s own pre-1943 closure to historical-critical methodologies" and "holds that upholding the divine authorship of a sacred text is a hindrance to theological dialogue." If such belief in divine authorship prevents its adherents from theological dialogue, then the Cardinal would have the same dialogical inhibitions that he imagines Muslim scholars to have. . . .See also: Scholars troubled by Vatican official's remarks on Muslim dialogue Catholic News Service. October 31, 2007: Jesuit Fr Daniel A. Madigan, who serves as a consultant to the commission for relations with Muslims at the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue said many Christians misunderstand how Muslims view the Quran, leading to a widespread prejudice that assumes Muslims are unwilling or incapable of interpreting the Quran. Further Catholic Responses Muslims have been waiting a response "from the top" to the letter, but that is not to say Catholics haven't responded -- individually (Fr. Samir Khalil, Fr. Troll, Cardinal Scola) and collectively (USCCB).

This letter is one of the most authoritative statements we have seen from Muslim leaders supporting dialogue and friendship between Christians and Muslims, based on a shared belief in God as the God of love, and in the commandment to love our neighbour as we love ourselves. [...]  George Weigel, on the other hand, is less than hopeful about the prospects of dialogue -- also taking note of the omission of the Pope's December address to the Roman Curia) ("A Disappointing Call for Dialogue" The Catholic Difference. November 7, 2007): George Weigel, on the other hand, is less than hopeful about the prospects of dialogue -- also taking note of the omission of the Pope's December address to the Roman Curia) ("A Disappointing Call for Dialogue" The Catholic Difference. November 7, 2007):For unless Islam can find within its own spiritual resources a way to legitimate religious freedom and the distinction between religious and political authority, the relationship between two billion Christians and a billion Muslims is going to remain fraught with tension. "A Common Word" speaks at length about the two Great Commandments; it says nothing about their applicability to issues of faith, freedom, and the governance of society: issues posed, for example, by the death threats visited upon Muslims who convert to Christianity and by the refusal to allow Christian public worship in Saudi Arabia. "A Common Word" also seems rather defensive, as if it were 21st century Christians who, in considerable numbers, were justifying the murder of innocents in advancing the cause of God. But that is manifestly not the case. . . . In the latest issue of Oasis, Paolo Branca, Senior Researcher and Assistant Professor in Arabic and Islamic Studies at the Catholic University of Milan, hails the document as "A Word to be Read and Spread in the Muslim World": As we are aware, the Islamic authorities are often influenced by the regimes of the countries where they live, but on this occasion it would seem that the need not to interrupt communication at a religious level has prevailed in respect of any potential reticence or orientations, more or less imposed. Indeed, the document does not linger on the polemic points which have predominated in the preceding intervention but seeks to return to the essence of the two respective traditions in order to identify common elements. . . .  In "The Christians of Arabia Wonder about the Open Letter", Bishop Paul Hinder, OFM Cap, believes that the letter "should not be left without a positive answer from the Christian side, although there are many open questions": In "The Christians of Arabia Wonder about the Open Letter", Bishop Paul Hinder, OFM Cap, believes that the letter "should not be left without a positive answer from the Christian side, although there are many open questions":Every effort to draw closer to a common understanding is welcome, even though it might be a very tiny beginning. Of course, there has to be further clarification about whether "the love of God" and the "love of neighbour" have the same meaning in both religions. Another crucial point might be that Christians cannot simply see Jesus Christ as one among other prophets, but profess him in his divinity as the living Son of God within the belief in One God in three Persons. However, the open letter can be a first important step in discovering a common ground that will later allow also a common word. Will this word also be a clear one, and not only a common one?Howbeit expressing his concern about the omission of the Jews from the document: The lack is the more regrettable as the central importance of the Jews today is crucial because of the political situation in the Middle East, a question requiring an answer which may be found at least partially in the application of the two main commandments by all who are involved. A common word should therefore include also the Jews.[According to the FAQ accompanying the letter: "Jewish scriptures are invoked repeatedly and respectfully in the document by way of preparing the ground for a further document specifically addressed to Jewish scholars" and "the problems between Jews and Muslims are essentially political not theological" -- I'm curious to see how this plays out]. Discussions on Catholic Blogs Returning to the blogosphere, DarwinCatholic and Wheat & Reeds have responded thoughtfully to my posts on this subject. I'll try to respond in kind. First, in Peace Through Strength In The Muslim World, Wheat and Weeds wonders: "To what extent do we owe this letter --which I take as meaningful and a sign of progress-- precisely to the Iraq war, since Muslims don't make the distinction we do between faith and politics?" -- recalling an earlier column by John Allen, Jr. on Christian-Muslim relations in Nigeria. According to the general secretary of the Christian Association of Nigeria, it was only when Christians responded with firm resolve and defended themselves against Muslim-initiated violence that they saw the need to come to the table: "They saw our people have resolve, and that's when the decision was made to form a consultative forum of religious leaders." Along the same lines: . . . while the letter is ostensibly a response to Benedict XVI's Regensberg lecture, and I take nothing away from the Pope --I think his "hard line" (really just a hard question) provoked this response, I wonder if we don't have to see Benedict & Bush as a tag team in favor of Muslim moderation, as Reagan and JP the Great overcame Soviet Communism. I am certainly appreciative of the firm resolve of the Bush Administration in waging a war against Al Qaeda and Islamic terrorism, which in Iraq finally seems to be bearing some fruit along these lines. (Writing for The Long War Journal Nov. 17, 2007 -- Bill Roggio reported that prominent Sunni clerics, who once supported, justified, or remained silent about al Qaeda's terror tactics, have now turned on the leading Sunni religious establishment that supports al Qaeda in Iraq). On the other hand, this is not to say that a good number of Muslims on their own initiative have been moved to reflect on the religious perversions that culminated in the horror of 9/11 and subsequent atrocities across the globe, or have repudiated unjust bloodshed in Allah's name.

Today, to reform is seen as a major way to purge extremism, but it is precisely through reform that extremist groups such as Al Qaeda are able to construct their jihadist worldview and claim legitimacy. In addition, the extremists and the reformers share some commonalities. Both want the right to reinterpret Islam as they see fit which can only be achieved by dismissing Islamic tradition. By doing so, both vest every Muslim with the competence to be a jurist. At the heart of both the extremist and reformist understanding of Islam is the individual and the self: there is no need to study the traditional Islamic sciences nor is there any need for recourse to the learned scholars as these give way to an "expression of a personal relationship [...] to faith and knowledge." It should come as no suprise, then, to learn that "few Al Qaeda operatives [...] have a religious education," [with] most having been trained within secular institutions and in technical fields, and it is extremely telling that Osama bin Laden referred to the 9/11 hijackers as belonging to no traditional school of Islamic law.(The State We Are In p. 26) It was toward this end that The Amman Message was conceived. Convened by an international Islamic summit to establish a consensus as to "what Islam does and does not allow, who is a Muslim and who can speak for Islam": First, the declaration recognized the legitimacy and common principles of all eight of the traditional schools of Islamic religious law (madhhabs) from the Sunni, Shi’i and Ibadi branches of Islam, and of Su, Ash’ari and moderate Sala Islamic thought. Second, it defined the necessary qualifications and conditions for issuing legitimate fatwas. This, in and of itself, defines the limits and borders of Islam and Islamic behavior. Amongst other things, it exposes the illegitimacy of the so-called ‘fatwas’ extremists use to justify terrorism, as these invariably contravene traditional Islamic sacred law (Shari’ah) and betray Islam’s core principles. Third, the declaration condemned the practice known as takfir (calling others “apostates”), a practice that is used by extremists to justify violence against those who do not agree with them.What is the potential of such a consensus? -- According to the website: This amounts to a historical, universal and unanimous religious and political consensus (ijma') of the Ummah (nation) of Islam in our day, and a consolidation of traditional, orthodox Islam. The significance of this is: (1) that it is the first time in over a thousand years that the Ummah has formally and specifically come to such a pluralistic mutual inter-recognition; and (2) that such a recognition is religiously legally binding on Muslims since the Prophet (may peace and blessings be upon him) said: My Ummah will not agree upon an error (Ibn Majah, Sunan, Kitab al-Fitan, Hadith no.4085).Something that may (we hope) bear some good fruit over time. In A Common Word: Islam and the Limits of Dialogue, DarwinCatholic expresses his reservations about the kind of "dialogue" anticipated by the signatories to "A Common Word": While I respect the sincerity of the signatories of A Common Word, and agree that the three great monotheistic religions do share in common principles of love of God and love of neighbor, I'm not clear how much of the deeper dialogue which they wish the Vatican were more open to is actually possible. For once we have discussed the love of God and love of neighbor, where exactly could we go from there? The one-ness of God, it would seem, and yet here we immediately run into one of the great historic differences between our faiths. Islam does not admit as possible that God should be three in one. And while explaining the Trinity in such terms as to be understandable to a Muslim audience would be a worthy occupation, if a consensus on this were achieved my understanding is that this would consist (for the Muslims) of rejecting traditional Islam. You cannot, so far as I can understand, both accept the trinity and be a good Muslim.We certainly cannot bridge the gap between the Muslim conception of Allah and Christianity's own Trinitarian convictions with fine words and diplomatic niceties. To concur with Fr. Troll, Christianity's Trinitarian convictions are ". . . not an aspect of Christianity that can be negotiated away. In this regard there are some slight ambiguities in the Open Letter, moments at which a Christian might feel that it is suggesting that there are no fundamental differences between the theologies of the two faiths, or at least that these differences do not really matter. While the warm, inviting tone of the Open Letter’s appeal to Christians is enormously encouraging, it is to be hoped that this can be held together with an approach which takes utterly seriously the points at which Christians and Muslims differ and does not encourage a diplomatic evasion of these points for the sake of a dialogue which would suffer as a result.However, I am not wholly convinced that the intent of the signatories is a veiled call for conversion. As mentioned in my first post, the document ends with an Islamic theological affirmation of religious pluralism: For each We have appointed a law and a way. Had God willed He could have made you one community. But that He may try you by that which He hath given you (He hath made you as ye are). So vie one with another in good works. Unto God ye will all return, and He will then inform you of that wherein ye differ. (Al- Ma’idah, 5:48)While I would not begrudge Muslims their desire to convert us (after all, don't we Christians have the 'Great Commission'?), the letter's conclusion (setting the stage for future discussions) present a challenge to those for whom the very existence of non-Muslims is considered intolerable. In this, "A Common Word" presents itself as a challenge to Muslims as well. To quote Dr. Nayed in his introduction to the letter: I whole-heartly believe that the true promise of this vital document, “A Common Word”, is that it is a first, but monumental step, toward retrieving and reliving the true Muslim way that was vividly described, long ago, by a spiritual master named Sidi Ahmed al-Rifa’i:Both Magister and Weigel reference in their writings the Pope's address to the Roman Curia as a basis for Christian-Muslim dialogue. Perhaps we should also take our cues from the Pope's address in November 2006 in meeting with Turkey's Religious Affairs Director, Ali Bardakoglu: Christians and Muslims belong to the family of those who believe in the one God and who, according to their respective traditions, trace their ancestry to Abraham [cf. Second Vatican Council, Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions Nostra Aetate, 1,3]. This human and spiritual unity in our origins and our destiny impels us to seek a common path as we play our part in the quest for fundamental values so characteristic of the people of our time. As men and women of religion, we are challenged by the widespread longing for justice, development, solidarity, freedom, security, peace, defence of life, protection of the environment and of the resources of the earth. This is because we too, while respecting the legitimate autonomy of temporal affairs, have a specific contribution to offer in the search for proper solutions to these pressing questions.Here, Benedict's message encompasses both the essential goal of "A Common Word" (addressing "the meaning and purpose of life, for each individual and for humanity as a whole" and identifying that which Christians and Muslims have in common -- love of God and neighbor, AND the framework in which that love is to be manifested: "freedom of religion, institutionally guaranteed and respected in practice." Q: Is the dialogue anticipated by Nayed really "entirely different" from that envisioned by the Pope?

|

Against The Grain is the personal blog of Christopher Blosser - web designer

and all around maintenance guy for the original Cardinal Ratzinger Fan Club (Now Pope Benedict XVI).

Blogroll

Religiously-Oriented

"Secular"

|

|

"The Pope likes New York and what it stands for", asserts Jeff Israely in a rather decent article on the Roman Pontiff by the American press (

"The Pope likes New York and what it stands for", asserts Jeff Israely in a rather decent article on the Roman Pontiff by the American press ( Describing Tocqueville as “le grand penseur politique,“ the context of these remarks was Ratzinger's insistence that free societies cannot sustain themselves, as Tocqueville observed, without widespread adherence to ”des convictions éthiques communes.“ Ratzinger then underlined Tocqueville's appreciation of Protestant Christianity's role in providing these underpinnings in the United States. In more recent years, Ratzinger expressed admiration for the manner in which church-state relations were arranged in America, using words suggesting he had absorbed Tocqueville's insights into this matter.

Describing Tocqueville as “le grand penseur politique,“ the context of these remarks was Ratzinger's insistence that free societies cannot sustain themselves, as Tocqueville observed, without widespread adherence to ”des convictions éthiques communes.“ Ratzinger then underlined Tocqueville's appreciation of Protestant Christianity's role in providing these underpinnings in the United States. In more recent years, Ratzinger expressed admiration for the manner in which church-state relations were arranged in America, using words suggesting he had absorbed Tocqueville's insights into this matter.  Times have changed, however -- no longer a Christian institution,

Times have changed, however -- no longer a Christian institution,

Responding to the protests of faculty members and students, Pope Benedict XVI cancels his appearance at Sapienza University.

Responding to the protests of faculty members and students, Pope Benedict XVI cancels his appearance at Sapienza University.

Calling the Sapienza protests a "painful blow to the entire city of Rome,"

Calling the Sapienza protests a "painful blow to the entire city of Rome,"  Agence France-Presse (AFP) reports that

Agence France-Presse (AFP) reports that

Update

Update  In section 23, Benedict again returns to the core message of his Regensburg address -- not a commentary on Islam (as emphasized by the press) but rather the restoration of reason to its proper place, in relation to faith:

In section 23, Benedict again returns to the core message of his Regensburg address -- not a commentary on Islam (as emphasized by the press) but rather the restoration of reason to its proper place, in relation to faith: Benedict counters the criticism that Christianity's promise of eternal life is "falling back once again into an individualistic understanding of salvation":

Benedict counters the criticism that Christianity's promise of eternal life is "falling back once again into an individualistic understanding of salvation": "How can Christians learn, articulate and exercise this hope in Christ? -- Benedict responds: "A first essential setting for learning hope is prayer." When no one listens to me any more, God still listens to me. When I can no longer talk to anyone or call upon anyone, I can always talk to God." He refers to Augustine's example of stretching, expanding, purifying our hearts of vinegar to make room for God's honey.

"How can Christians learn, articulate and exercise this hope in Christ? -- Benedict responds: "A first essential setting for learning hope is prayer." When no one listens to me any more, God still listens to me. When I can no longer talk to anyone or call upon anyone, I can always talk to God." He refers to Augustine's example of stretching, expanding, purifying our hearts of vinegar to make room for God's honey. That said,

That said,  Cardinal Pell of Australia also mentioned the letter recently, in an address entitled

Cardinal Pell of Australia also mentioned the letter recently, in an address entitled