|

||

|

||

|

Thursday, November 13, 2008

Thomas Merton, American Catholic

By way of Carl Olson comes Can You Trust Thomas Merton? - an evaluation of the Trappist monk and contemplative Thomas Merton which appears in This Rock, by Dr. Anthony E. Clark. By way of Carl Olson comes Can You Trust Thomas Merton? - an evaluation of the Trappist monk and contemplative Thomas Merton which appears in This Rock, by Dr. Anthony E. Clark.

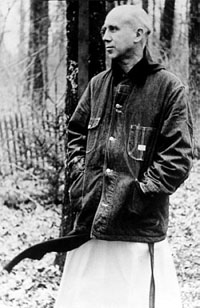

As with most critical evaluations of Merton, Clark mentions some by-now-familiar pieces of controversy in Merton's life -- His fathering a child during his hedonistic and womanizing years in Cambridge, where to quote him directly, he "labored to enslave myself in the bonds of my own intolerable disgust" and his on-again, off-again relationship with his superior, abbot Dom James Fox. But it is not so much Merton's "sins of the flesh" which are perceived as a danger (something which even the greatest saints were certainly not immune -- is it more than coincidence that Merton's Hindu friend Brahmachari would recommend Augustine's Confessions?) as his exploration of the world's religions, particularly Buddhism, the character of which, according to Dr. Clark, "often appears more like replacement than rapprochement." Merton's life was tragically cut short during his Asian journey, but he died insisting that "Zen and Christianity are the future," and that "if Catholics had a little more Zen they’d be a lot less ridiculous than they are." According to Dr. Clark, while it be "would be unfair to call Merton an unfaithful Catholic, or to insist that he became a Buddhist before his death," his ideas, particularly those expressed in later writings should be read with caution as they are likely to be "more confusing than helpful, for they conflate and confuse Buddhist and Christian teachings." * * * The writings of Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day were both very influential in my own early college years as a budding Catholic (I was received into the Church my junior year). Like Dr. Clark I have little reservations about recommending his earlier, "orthodox" works, and adding a caution to his later ones. This is not to say that one may not benefit from the latter, but rather -- to concur with Justin Nickelson's comment on Olson's post, "not everybody is in a position to, perhaps, separate the 'wheat from the chaff' in theological, spiritual, philosophical writings. Thus, perhaps being safe than sorry is a good thing."That said, some additional thoughts: I do not think a Catholic interest in, and personal investigation of, Buddhism (or any other religion) is not in itself something that we should regard as inherently suspect. Not to infer this of the author of the present article (Dr. Clark reveals that he is presently "living in China doing, among other things, research on authentic Buddhist teaching" and has just recently returned from a residence in a Tibetan Buddhist village in the Himilayas) -- but that this is the unfortunate impression received from certain commentators on Carl Olson's post, suggesting that Merton's investigation of Buddhism was an indication that he had "gone wobbly": He seems not to have placed full trust in Christ but instead to have gone off and looked for the truth elsewhere. How else can one explain his dalliance with Eastern religion?I think this is a great injustice to Merton and again, concur with Justin: "if one hasn't read any of Merton or other authors, or, worse, hasn't read anything at all, they must be careful: Slander is applicable to 'dead theologians' as well." Those familiar with Merton's writings will uncover passages even in his later works which call into question the assumption that he "strayed from the faith". Let us consider but two passages -- the first by way of Teófilo (Vivificat!), from 1965, which reveals Merton's "Theo-centric and Christo-centric" approach in the midst of his Eastern investigations: The Feast of the Sacred Heart was for me a day of grace and seriousness. Twenty years ago I was uncomfortable with this concept. Now I see the real meaning of it (quite apart from the externals). It is the center, the "heart" of the whole Christian mystery. (Source: Dancing in the Water of Life: The Journals of Thomas Merton (1953-1965). Secondly, consider a passage from one of Merton's books which bear This Rock's admonition to "read with caution" -- one of my favorites, in fact: Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander But has the concept of heresy become completely irrelevant? Has our awareness of the duty of tolerance and charity toward the sincere conscience of others absolved us from the danger of the error ourselves? Or is error something we no longer consider dangerous? I think a Catholic is bound to remember that his faith is directed to the grasp of truths revealed by God, which are not mere opinions or "manners of speaking," mere viewpoints which can be adopted and rejected at will -- for otherwise the commitment of faith would lack not only totality but even seriousness. The Catholic is one who stakes his life on certain truths revealed by God. If these truths cease to apply, his life ceases to have meaning. Strange that this very book -- selections culled from Merton's personal writings during the 1960's and arranged by Merton himself in 1965 -- was published in 1968, the same year that Merton embarked on his "Eastern journey" to Asia and "drifted" from Christianity. Yes, Merton was open to new aspects and dimensions of the Catholic faith -- he was eager to reach out to others, and his writings are a treasure of engagements with nonbelievers and believers of all religions: Christian and non-Christian. (Not as well known, but no less interesting, is Merton's interest in Sufism -- by way of his correspondence with the Franciscan scholar of Islam Louis Massignon and later, with the Pakistani Abdul Aziz). But -- at the cost of abandoning his Christian faith? The suggestion that Merton would see fit to include a lengthy passage from his journals sharply critical of a spiritual relativism that denies the fundamental claims of Christianity . . . and then proceed a few years later to rush headlong towards the East -- away from the Incarnated and Risen Christ -- seems to me rather tenuous.

Because Merton was drawn to develop relationships with non-Christians -- Jews, Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists -- casual readers occasionally form the impression that Merton's bond with Christianity was wearing thin during the latter years of his life and that he was window-shopping for something else. It is not unusual to meet people who think that, had he only lived longer, he would have become a Buddhist. But as you get to know Merton's life and writing more intimately, you come to understand that his particular door to communion with others was Christ Himself. Apart from times of illness, he celebrated Mass nearly every day of his life from the time of his ordination in 1949 until he died in Thailand 19 years later. Even while visiting the Dalai Lama in the Himalayas, he found time to recite the usual Trappist monastic offices. One of the great joys in the last years of his life was his abbot permitting the construction of a chapel adjacent to the cider block house that became Merton's hermitage -- he was blessed to celebrate the Liturgy where he lived. If there were any items of personal property to which he had a special attachment, they were the several hand-written icons that had been given to him, one of which traveled with him on his final journey. Few people lived so Christ-centered a life. But his Christianity was spacious. The Dalai Lama has remarked, "When I think of the word Christian, immediately I think -- Thomas Merton!" ["Thomas Merton, His Faith and His Time" lecture given at Boston College 13 November 1995]There is no question that Merton's years on this earth were as tumultuous as the times. He was a Trappist monk commmitted to the pursuit of solitude and contemplation, and at the same time a prolific writer (encouraged in part by his superiors) with an understandable interest in the issues occupying the world outside the monastery gates: the civil rights movement; the proliferation of nuclear arms; the Vietnam war. He was a hermit, residing in a toolshed in the Kentucky woods; and yet his life was replete with a perpetual stream of visitors (and an even greater flood of correspondence). He held these and many other facets of his life in constant tension. As Robert Royal says in The Several Storied Thomas Merton (First Things February 1997): "a kind of multiple personality disorder keeps turning up in writers—and writers with a religious bent seem particularly susceptible ... of all the great modern religious writers, no one harbored within himself a larger cast of dramatis personae than Thomas Merton." I think this complexity -- the interplay of dueling roles -- is a significant reason for his appeal, particularly in modern-day America. When I examine my own life and the many roles which I occupy even on a daily basis (son, brother, husband, father, worker, friend ... blogger) -- and throughout, the struggle to keep my feet planted on the ground, spiritually speaking; to mirror Christ as best I can (oftentimes failing rather terribly) -- I find myself deeply sympathetic to Merton's lifelong ambition to stay the course; to pray, as he did: My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going. I do not see the road ahead of me. I cannot know for certain where it will end. Nor do I really know myself, and the fact that I think I am following your will does not mean that I am actually doing so. But I believe that the desire to please you does in fact please you. And I hope I have that desire in all that I am doing. I hope that I will never do anything apart from that desire. And I know that if I do this you will lead me by the right road, though I may know nothing about it. Therefore I will trust you always though I may seem to be lost and in the shadow of death. I will not fear, for you are ever with me, and you will never leave me to face my perils alone.How many of us can relate to this prayer? In closing, again, Robert Royal: Merton's true greatness lies in having engaged in person the whole range of challenges and trials of life in the late twentieth century and yet remaining essentially faithful to his Catholic inspiration. Many of those issues we still confront: poverty and war, the relationship of Eastern and Western thought, and especially how a deep religious life may be lived in contemporary conditions. As we near the end of the century, religion-even contemplative practices-have had a tremendous resurgence. Many of the paths religious people took during the 1960s are coming more and more to look like a dead end. But the attempt to bring a deeper spirituality to the public realm-to say nothing of recovering authentic spirituality-remains a burning necessity. Back in 2004 the USCCB decided to strike Thomas Merton from their National Adult Catechism, to the great protest of many American Catholics. I responded with Towards a Critical Appreciation of Thomas Merton (Against The Grain January 2, 2005), which served as a basis for this current post. Labels: merton

Sunday, January 09, 2005

Thomas Merton Revisited

I came across (and posted) this excerpt from Merton's journals last year, but in light of the reception of my recent post, I think some of my (newer) readers would find it interesting: I came across (and posted) this excerpt from Merton's journals last year, but in light of the reception of my recent post, I think some of my (newer) readers would find it interesting:In the climate of the Second Vatican Council, of ecumenism, of openness, the word "heretic" has become not only unpopular but unspeakable -- except, of course, among integralists, who often deconstruct their own identity on accusations of heresy directed at others.

But has the concept of heresy become completely irrelevant? Has our awareness of the duty of tolerance and charity toward the sincere conscience of others absolved us from the danger of the error ourselves? Or is error something we no longer consider dangerous? I think a Catholic is bound to remember that his faith is directed to the grasp of truths revealed by God, which are not mere opinions or "manners of speaking," mere viewpoints which can be adopted and rejected at will -- for otherwise the commitment of faith would lack not only totality but even seriousness. The Catholic is one who stakes his life on certain truths revealed by God. If these truths cease to apply, his life ceases to have meaning. A heretic is first of all a believer. Today the ideas of "heretic" and "unbeliever" are generally confused. In point of fact the mass of "post-Christian" men in Western society can no longer be considered heretics and heresy is, for them, no problem. It is, however, a problem for the believer who is too eager to identify himself with their unbelief in order to "win them for Christ." Where the real danger of heresy exists for the Catholic today is precisely in that "believing" zeal which, eager to open up new aspects and new dimensions of the faith, thoughtlessly or carelessly sacrifices something essential to Christian truth, on the grounds that this is no longer comprehensible to modern man. Heresy is precisely a "choice" which, for human motives . . . selects and prefers an opinion contrary to revealed truth as held and understood by the Church. I think, then, that in our eagerness to go out to modern man and meet him on his own ground, accepting him as he is, we must also be truly what we are. If we come to him as Christians we can certainly understand and have compassion for his unbelief -- his apparent incapacity to believe. But it would seem a bit absurd for us, precisely as Christians, to pat him on the arm and say "As a matter of fact I don't find the Incarnation credible myself. Let's just consider that Christ was a nice man who devoted himself to helping others!" This would, of course, be heresy in a Catholic whose faith is a radical and total commitment to the truth of the Incarnation and Redemption as revealed by God and taught by the Church. . . . What is the use of coming to modern man with the claim that you have a Christian mission -- that you are sent in the name of Christ -- if in the same breath you deny Him by whom you claim to be sent? Thomas Merton Conjectures is a compilation of Merton's notes and spiritual reflections during the 1960's, and was first published in 1968, the same year Merton had, according to Msgr. Michael J. Wrenn and Kenneth D. Whitehead, "drifted away from the faith" and had fled to Asia to become a Buddhist. As Teófilo (Theophilus) (Vivificat) noted in his comments on my original post, "Theologically, though, one needs to read Merton's journals to get the feel on how conservative he really was. Again, the key is found in his journals." On the subject of "Vindicating Thomas Merton," Teófilo posts another remarkable excerpt from Merton's journals (June 6, 1965), in which he specifically comments on his "interest in the East." What Merton says in response is in itself an affirmation of the 'Christo-centric' nature of his reflections, even in the very last months of his life. Labels: merton

Sunday, January 02, 2005

Towards a Critical Appreciation of Thomas Merton

A little more than a year ago, Msgr. Michael J. Wrenn and Kenneth D. Whitehead voice their disappointment with the inclusion of Thomas Merton in the draft of the new National Adult Catechism in an article for Catholic World News (The New National Adult Catechism Revisited CWNews, Nov. 2003). Their article contained a blatantly slanderous and damning portrayal of Thomas Merton as an unfaithful Catholic: A little more than a year ago, Msgr. Michael J. Wrenn and Kenneth D. Whitehead voice their disappointment with the inclusion of Thomas Merton in the draft of the new National Adult Catechism in an article for Catholic World News (The New National Adult Catechism Revisited CWNews, Nov. 2003). Their article contained a blatantly slanderous and damning portrayal of Thomas Merton as an unfaithful Catholic:. . . we now turn immediately to the very first "story" in Part 1, Chapter 1, of the draft NAC, and we find that, incredibly, the supposed "exemplary Catholic" featured in this first story is none other than that lapsed monk, Thomas Merton, a one-time professed Catholic religious, who later left his monastery, and, at the end of his life, was actually off wandering in the East, seeking the consolations, apparently, of non-Christian, Eastern spirituality. Now it is true that Thomas Merton was a gifted writer, which in part explains why he continues to have votaries today; he wrote beautiful words about the needs of the human heart in its search for truth and grace. Some of these words are quoted here, and apparently were the pretext for featuring Merton in this chapter. The chapter is actually richer than that, though, and features at the end some wonderful quotations from St. Augustine. Blogger and fellow member of St. Blog's Parish Bill Cork has recently defended Merton against the slander that he had "left the Church", pointing out that: Merton was not a "lapsed monk," nor a "one-time professed Catholic religious," nor did he ever leave his monastery. He remained a faithful Catholic and a faithful member of the Trappists until he died; he is buried at Gethsemane as "Fr. Louis." He was not "actually off wandering in the East," but went to Thailand for a conference of Christian and Eastern monks, and had other dialogues with leaders of Eastern religions along the way; he died at the Thailand conference when he accidentally pulled an electric fan onto himself. This is simple history known to anyone who knows anything about Merton. Unfortunately, Wrenn & Whitehead's critical article is now suspected as having contributed to the decision of the U.S. Bishops to replace the profile of Merton with American Catholic Elizabeth Ann Seton (the rationale being: "to provide more gender balance, because most of the other profiles [included in the catechism] are of men"). Merton's rejection has sparked protest of hundreds of Catholics, as reported by the Louisville Courier ("Hundreds want Merton back in Catholic guide" January 1, 2005) and monitered by Dan Phillips, who runs a popular website on all things Merton). The International Merton Society has released open letter to Bishop Donald Wuerl, chair of the committee charged with writing the catechism, and USCCB president Bishop William Skylstad, questioning Donald Wuerl's claim that "we don't know all the details of the searching at the end of his life": As for the "secondary" consideration ". . . we are aware of no reputable Merton scholars or even of careful readers of Merton who think that his interest in Eastern religions toward the end of his life, which led to his Asian journey and his untimely death, in any way compromised his commitment to the Catholic Christianity that he had embraced thirty years before. On the contrary, a reading of the major biographies by James Forest, Michael Mott and William Shannon, of The Other Side of the Mountain, the final volume of his journals, of his retreat conferences in Thomas Merton in Alaska, given immediately before leaving for Asia, and of his final talk on the day of his death, published in The Asian Journal, confirm that it was because of the deep grounding in his own Catholic, Cistercian, contemplative tradition that he was able to enter into meaningful dialogue with representatives of other religious traditions like the Dalai Lama, who has repeatedly said that it was his encounter with Merton that first allowed him to recognize the beauty and authentic spiritual depths of Christianity.  If that wasn't enough to persuade Wrenn & Whitehead, let's hear a refutation from Jim Forest himself [photo, left], from a lecture given at Boston College (Nov. 13, 1995): Because Merton was drawn to develop relationships with non-Christians -- Jews, Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists -- casual readers occasionally form the impression that Merton's bond with Christianity was wearing thin during the latter years of his life and that he was window-shopping for something else. It is not unusual to meet people who think that, had he only lived longer, he would have become a Buddhist. But as you get to know Merton's life and writing more intimately, you come to understand that his particular door to communion with others was Christ Himself. Apart from times of illness, he celebrated Mass nearly every day of his life from the time of his ordination in 1949 until he died in Thailand 19 years later. Even while visiting the Dalai Lama in the Himalayas, he found time to recite the usual Trappist monastic offices. One of the great joys in the last years of his life was his abbot permitting the construction of a chapel adjacent to the cider block house that became Merton's hermitage -- he was blessed to celebrate the Liturgy where he lived. If there were any items of personal property to which he had a special attachment, they were the several hand-written icons that had been given to him, one of which traveled with him on his final journey. Few people lived so Christ-centered a life. But his Christianity was spacious. The Dalai Lama has remarked, "When I think of the word Christian, immediately I think -- Thomas Merton!" Merton - Conventional Catholic and Otherwise Whatever position one takes in the present debate, it must be recognized that Merton was anything but a conventional Trappist monk. On one hand, Merton very much catered to such a portrayal as a "traditional" Catholic -- he wrote a spiritual biography heralded as one of the most influential religious works of the twentieth century (The Seven Storey Mountain, 1948); he produced lengthy meditations on traditional Catholic subjects like the Eucharist (The Living Bread, 1956), the Carmelite spirituality of St. John of the Cross (The Ascent to Truth, 1951) and the monastic calling (The Silent Life, 1957). On the other hand, the latter period of Merton's relatively brief life did everything to call his portrayal as a "traditional Catholic" into question: he ventered into political activism in the 1960's (protesting the Vietnam war, racial segregation and the nuclear arms race); displayed a genuine interest in other religions and engaged in dialogue with their practicioners (including D.T. Suzuki, Thich Nhat Hanh, and the Dalai Lhama) in a spirit that anticipated Vatican II's Nostra Aetate, and journeyed to Japan and India to attend conferences on Buddhist-Christian dialogue. There is no denying that the later Merton had changed to some degree in his thought and attitude toward the Catholic Church. In fact, according to Merton's friend Edward Rice, he went on to say I have become very different than what I used to be. The man who began this journal [The Sign of Jonas] is dead, just as the man who finished The Seven Storey Mountain when this journal began is also dead, and what is more, the man who was the central figure in The Seven Story Mountain was dead over and over . . . The Seven Story Mountain is the work of a man I had never even heard of." [The Man in a Sycamore Tree, p 101]. The remark can be interpreted on a number of levels. Rice interprets it as a sign of Merton's disappointment with Trappist life, that it did not bring the peace and contentment he had envisioned when initially becoming a monk. But perhaps Merton's statement can be read as well as a sign of his personal exasperation with Seven Storey Mountain, which propelled him into the public eye and branded him as a kind of "poster boy for American Catholicism" sought after by thousands of adoring readers -- not an easy situation for a Trappist monk attempting to live a life of solitude, seeking to relenquish his ego in the quest for God. However much we may appreciate Seven Storey Mountain, one can also recognize an underlying current of pious revulsion at the secular world, a distinct attitude which laid the groundwork for further change -- as can be seen by Merton's account of his spiritual epiphany en route to the city of Louisville in The Sign of Jonas:The Sign of Jonas: I wondered how I would react at meeting once again, face to face, the wicked world. I met the world and found it no longer so wicked after all. Perhaps the things I resented about the world when I left it were defects of my own that I had projected upon it. Now, on the contrary, I found that everything stirred me with a deep and mute sense of compassion . . . I seemed to have lost an eye for merely exterior detail and to have discovered, instead, a deep sense of respect and love and pity for the souls that such details never fully reveal. I went through the city, realizing for the first time in my life how good are all the people in the world and how much value they have in the sight of God."  The Universal Appeal of Thomas Merton Jim Knight and Edward Rice, two of Merton's close friends, published an online recollections of their memories of Merton -- The Real Merton -- resisting the characterization of their friend as a triumphant Catholic ("a portrait that was unrecognizable, that of a plastic saint, a monk interested mainly in pulling nonbelievers, and believers in other faiths, into the one true religion"). According to Knight and Rice: The Merton we knew, who is still in the lives of both of us, was a different man, and monk, from the saintly person of pre-fabricated purity that has become his image these days. He was a real person, not a saint; he was a mystic searching for God, but a God that crossed the boundaries of all religions; his was not a purely Christian soul. He developed closer spiritual ties than Church authorities will ever admit to the Eastern religions, Hinduism as well as Buddhism. In fact just before his appalling accidental death in December 1968, he was saying openly that Christianity could be greatly improved by a strong dose of Buddhism and Hinduism into its faith. These are things the record needs. Edward Rice, who sponsored Merton's conversion, goes on to challenge what he calls the "Thomas Merton Cult": "['The Thomas Merton cult'] presents Merton as a plastic saint," Rice says, "a contemporary Little Flower, a sweet, sinless individual who has a direct line to God. But the God some people see Merton communicating with is not the God that I think Merton would have been praying to. I am not comfortable with the plastic saint image of Merton; he was no such thing. I see Merton as an individual in the grand scheme, and it makes no difference whether he is approached as a Roman Catholic monk or a Buddhist lama. He was Merton, and he has his influence as Merton." Granted, Rice's vision of salvation may be deemed more universalistic and non-traditional than most Catholics ("in Paradise with Merton, Rice says, are Lao Tse, Isaac the Blind, Ibn el Arab[i], Confucius, Thomas Aquinas, Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King, Charles de Foucau[l]d, . . . "an endless number, hundreds, thousands of saints of all faiths, some with no faith at all"), and I am not altogether certain where such a "Thomas Merton Cult" is to be found (the appreciations I've read of Merton readily acknowledge his defects in character), but I believe he is nevertheless correct in challenging those who seek to claim Merton entirely as Catholic, who could only be appreciated in the context of Catholicism and denying his universal appeal by other religious, or even non-religious folk. Merton's Interest in Other Religions - Two Closing Observations

For one thing, the young Merton was impressed by the spiritual conversion of Alduous Huxley (from materialism to mysticism recognizing "a divine Reality substantial to the world of things and lives and minds . . . [as can be found] among the traditionary lore of primitive peoples in every region of the world, and in its fully developed forms it has a place in every one of the higher religions"), and who was fascinated by Huxley's investigation of mysticism in the world's religions The Perennial Philosophy. Likewise, it was at Columbia University, that Merton met a Hindu spiritual pilgrim -- Bramachari -- who first encouraged him to read St. Augustine's Confessions and The Imitation of Christ, and thus played a part in his journey to Catholicism. Both Merton's encounters with Huxley and Bramachari are described in The Seven Storey Mountain). According to Alexander Lipski (Thomas Merton and Asia: His Quest for Utopia), around the same time he met Bramachari Merton also was reading the Hindu scholar Ananda K. Coomaraswamy (initially in connection with his M.A. thesis on William Blake). Again, to borrow from Bill Cork, much of this is common knowledge to anybody who has studied Merton or has read Merton's biography. I suppose the real question here is not when did Merton begin to study Eastern religions, but rather to what degree did Merton's Catholicism inform and influence his post-Christian exploration of Eastern religions? -- Write and Wrenn have their own conclusions, but so do Robert Forest, Jim Knight, Edward Rice and a number of Merton scholars worldwide. That said, Merton's later writings on other religions -- particularly those on Buddhism -- should nevertheless be read with great care and critical judgement by the laity. Raymond Bailey (curiously, a Southern Baptist minister who became Director of the Thomas Merton Studies Center at Bellannine College in the early 80s) goes into detail as to why this caution is necessary in his study Thomas Merton on Mysticism (Doubleday Image, 1975). It's a little long, but worth repeating in full: Merton's writings on Eastern mysticism are tempered by repeated allusions to traditional Christian symbols. His diaries written in the last months he spent at the hermitage record his preferences for the Fathers for reading in the cottage and for the works of the Zen masters in the fields. However, his published works are not always instructive as to how the Zen experience can contribute to the Christian experience or how the study of Eastern religions or the practice of oriental techniques engender or complement the Christian experience. Some of his published works might well be interpeted as syncretistic and might leave the reader with the im pression that it does not matter what religious expression one's spirituality takes as long as it has broken through the facade of the illusionary self. Should Merton be recognized in the new American Catechism? When it comes to Merton, I find myself agreeing with Robert Royal, on why -- despite his apparent flaws -- we may regard Merton as worthy of praise: Merton's true greatness lies in having engaged in person the whole range of challenges and trials of life in the late twentieth century and yet remaining essentially faithful to his Catholic inspiration. Many of those issues we still confront: poverty and war, the relationship of Eastern and Western thought, and especially how a deep religious life may be lived in contemporary conditions. As we near the end of the century, religion-even contemplative practices-have had a tremendous resurgence. Many of the paths religious people took during the 1960s are coming more and more to look like a dead end. But the attempt to bring a deeper spirituality to the public realm-to say nothing of recovering authentic spirituality-remains a burning necessity. Does Merton deserve placement in the USCCB's Catechism for adult American Catholics? -- I'm inclined to think that Robert Royal might say yes for the reasons stated above, even with due respect to the concerns raised by Merton's interest in Eastern religions. I would answer in the affirmative as well, although I admit here to being a little biased in the matter, since it was through reading Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day that I discovered and was led to the Catholic faith in the first place. I would also question (if the Louisville Courier-Journal is correct) Bishop Wuerl's justification that young people "had no idea" who Merton was -- as if he were an eclectic relic of the early 20th century better swept underneath the rug, whose life and thought simply had no relevance for Catholics of today. Judging by the staying power of Merton in bookstores and conferences on Merton attended by those interested in "the silent life" of contemplation, perhaps Bishop Wuerl underestimates the prevalence Merton has in the hearts of the laity, and his influence (even today) in leading souls to the Catholic faith. Related Readings (Online and In Print):

Tuesday, June 10, 2003

In the climate of the Second Vatican Council, of ecumenism, of openness, the word "heretic" has become not only unpopular but unspeakable -- except, of course, among integralists, who often deconstruct their own identity on accusations of heresy directed at others. Thomas Merton Labels: food for thought, merton

Wednesday, May 07, 2003

The Witness of Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day

Amy Wellborn says that "if you are an American Catholic, Paul Elie's new book The Life You Save May Be Your Own belongs on your bookshelf, and, more importantly, belongs in your hands, open, being read" -- which may be reason enough to stop reading this, run to your bookstore and get a copy right now. I started it a couple days ago and am enjoying it immensely.

I've read mixed opinions of Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day by various members of St. Blog's parish, and they are indeed the most controversial of the American Catholic writers portrayed in Elie's book (the other two being Walker Percy and Flannery O'Connor). Merton's spiritual autobiography Seven Storey Mountain was well-recieved not only by the American public but readers around the world, through which he acquired a kind of 'celebrity status' as one of the most popular Catholic personalities in the twentieth century. However, his counter-cultural participation in the peace movement, sharp criticism of the U.S. during the Vietnam and Cold War tarnished his reputation in the eyes of those readers who percieved him as a traditional Catholic. Likewise, Merton's appreciation and engagement with Hinduism, Buddhism and Sufism in the later years of his life -- anticipating, I believe, the interreligious dialogue proposed by Vatican II's Nostra Aetate -- was heavily criticized and portrayed by some as an abandonment of his Catholic faith. There are many sides to Merton, as evidenced by the recollections of several close friends and discussed in Robert Royal's essay The Several-Storied Thomas Merton (First Things January 1997, pp. 34-38), and despite such criticism I find myself agreeing with Royal's assessment that: Merton's true greatness lies in having engaged in person the whole range of challenges and trials of life in the late twentieth century and yet remaining essentially faithful to his Catholic inspiration. . . . His personal turmoil and the misjudgments in his social thought notwithstanding, he is a forceful reminder that what may appear the most rarefied of contemplative speculations have powerful and concrete implications for the world. God dealt Thomas Merton a difficult hand. His greatness as a man lies not only in that he was able, more or less, to keep several different persons together in difficult times under the banner of "Thomas Merton," but that he provides an enduring witness to all of us much less gifted seekers who have to shore up our own fragmentary lives in quest for the "hidden wholeness." There is not a great deal in Dorothy Day's religious thought and behavior that would invite criticism from traditional Catholic critics. According to Jim Forest: Whether traveling or home, it was a rare day when Dorothy didn’t go to Mass, while on Saturday evenings she went to confession. Sacramental life was the rockbed of her existence. She never obliged anyone to follow her example, but God knows she gave an example. When I think of her, the first image that comes to mind is Dorothy on her knees praying before the Blessed Sacrament either in the chapel at the farm or in one of several urban parish churches near the Catholic Worker. One day, looking into the Bible and Missal she had left behind when summoned for a phone call, I found long lists of people, living and dead, whom she prayed for daily. However, like Merton, Dorothy Day was a prominent critic of modern culture, and her unwavering solidarity with and service to the poor, unflinching pacifism, and vehement criticism of Western capitalist consumerism placed her at odds with many in society, especially the economically-advantaged. Sadly enough, while some may have legitimate differences with Dorothy's politics, there are also critics who like to dredge up Dorothy's past, including the fact that she was a divorcee (from a "common-law" marriage) and had an abortion in her bohemian days. While they see this as grounds for opposition, I find it all the more reason to celebrate her life as a testimony to God's abundant grace and forgiveness. Perhaps they ought to listen to Cardinal O'Connor, who recognized that it was Dorothy's very opposition to abortion that made her an appropriate model for our time, and advanced the cause for her Beatification and Canonization in 1997. I encountered the writings of both Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day as a junior in college, then a lapsed Christian engaged in intellectual flirtation with existentialism, radical politics and Eastern religion. Zen & the Birds of Appetite was the first book of Merton's I ever read, and provided me with an impressive incredible example of how a Christian can engage in interfaith dialogue with clarity and wisdom. Shortly thereafter, curiousity aroused by conversations with a Catholic Worker friend, I read Dorothy Day's spiritual autobiography The Long Loneliness, and as one questioning whether religious faith and political commitment were in irrevocable conflict (aka. Marx), Dorothy provided a worthy example of how to integrate the two. I can honestly say that without the spiritual influence of both writers, I probably wouldn't be writing this blog today, and for that I'd heartily second Amy Welborn's recommendation. Labels: dorothy day, merton

|

Against The Grain is the personal blog of Christopher Blosser - web designer

and all around maintenance guy for the original Cardinal Ratzinger Fan Club (Now Pope Benedict XVI).

Blogroll

Religiously-Oriented

"Secular"

|

|

It would be mistaken to assume that Merton's interest in other religions was a post-conversion manifestation of his disappointment with Catholicism, as alleged by Msgr. Michael J. Wrenn and Kenneth D. Whitehead. I question this because Merton displayed an interest in the other religions (especially those of the East) from the time he was a college student at Columbia University.

It would be mistaken to assume that Merton's interest in other religions was a post-conversion manifestation of his disappointment with Catholicism, as alleged by Msgr. Michael J. Wrenn and Kenneth D. Whitehead. I question this because Merton displayed an interest in the other religions (especially those of the East) from the time he was a college student at Columbia University.